Fitzcarraldo

Another tangentially on-topic film went into the old DVD player the other night: Werner Herzog’s Fitzcarraldo (1982).

Another tangentially on-topic film went into the old DVD player the other night: Werner Herzog’s Fitzcarraldo (1982).

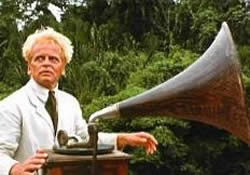

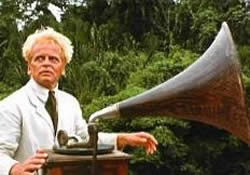

Klaus Kinski plays an obsessive visionary kook (shades of José Arcadio Buendía from One Hundred Years of Solitude, but with a crazed intensity that radiates from Kinski's every movement) with a passion for grand opera. An appearance by Enrico Caruso and Sarah Bernhardt at the Teatros Amazonas in Manaus stokes his latest dream: to build an opera house in the town further in the jungle’s interior in which he lives, and to have Caruso sing at the opening.

Fitzcarraldo doesn't really grasp the distance between dream and reality, a distance made vaster by the audacity of his visions. To make the money for his opera house, he enters the rubber business, optioning a plot of land made inaccessible by treacherous rapids and unfriendly natives. He hires his crew from the motley collection of laborers who are unemployed during boom times. Fitzcarraldo’s planned route to his land is virtually impossible. The whole project is ill-advised and destined for disaster.*

While the crew carries various guns and knives, Fitzcarraldo is armed with a stack of Caruso records and an unshakeable belief in his dream. When war drums echo through the jungle, he responds by cranking up his Victrola and serenading the natives with Verdi. And it works. (To Herzog’s credit the native tribe that Fitzcarraldo encounters is treated sensitively and with intelligence. They never become a surrogate for a lost Western ideal, and their motives remain their own even as they undertake the bizarrely

While the crew carries various guns and knives, Fitzcarraldo is armed with a stack of Caruso records and an unshakeable belief in his dream. When war drums echo through the jungle, he responds by cranking up his Victrola and serenading the natives with Verdi. And it works. (To Herzog’s credit the native tribe that Fitzcarraldo encounters is treated sensitively and with intelligence. They never become a surrogate for a lost Western ideal, and their motives remain their own even as they undertake the bizarrely impossible improbable task of hauling a steamship over a mountain.)

The movie has a great many scenes that are breathtakingly beautiful: huge old-growth rainforest trees crash into a river; a steamship emerges from dissipating fog at a 45-degree angle on the mountainside; the ship slams through an unnavigable stretch of rapids; plus the innumerable gorgeous shots of the Amazonian basin. The on-location scenery is large part of the mixture of reality and hallucination that makes the film spellbinding.

* To skim articles online, the same could be said for Herzog’s movie. It was shot on location, with real Indians, a histrionic leading man, a maniacal director and the Herculean labor at the heart of the film. There’s also a documentary called The Burden of Dreams (which I’m looking forward to tracking down) that details the “fever dream” of making Fitzcarraldo.

Dodge This

On a side note, one of Fitzcarraldo’s Caruso records is the famous “Vesti la giubba” from I Pagliacci. That recording is the source material for Charles Dodge’s piano + tape composition Any Resemblance is Purely Coincidental, which has to rank near the top of any list of “fun electro-acoustic pieces.”

On a side note, one of Fitzcarraldo’s Caruso records is the famous “Vesti la giubba” from I Pagliacci. That recording is the source material for Charles Dodge’s piano + tape composition Any Resemblance is Purely Coincidental, which has to rank near the top of any list of “fun electro-acoustic pieces.”

The pianist begins as Caruso’s accompanist, but as the piece progresses there are episodes of quasi-improvisational give and take and a passage of the arrangement for solo piano with obbligato processed Caruso. The game of humor (and gentle mockery) takes a twist to pathos in the coda, recasting the emotional payoff of one of the most clichéd moments in grand opera - the big climax at “Ridi, Pagliacco.” You can listen to the entire piece (8 minutes) at Art of the States.

Cheap or classy? You decide.

Pottery Barn cultivates the dead-stick aesthetic.

Trois couleurs

Easily the most productive thing I did during my week of temporary bachelorhood was visit ye olde local video store to rent Krzysztof Kieslowski’s Three Colors. Each film – Blue, White, and Red – represents an aspect of the tricolor French flag: liberté, egalité, fraternité. The colors appear symbolically throughout, often used enigmatically but also with a welcome subtlety. Despite the abstract concept Kieslowski deals with people – real, fully drawn characters, their relationships, and emotions. Liberté is explored via isolation; egalité is a battle of mutual humiliation; and Red finds fraternité that begins with invasions of privacy.

Part of the joy for me in Three Colors (besides the three beautiful women cast in each movie) is that composed music is significant in Kieslowski’s world. It isn’t used as window dressing or in a cheaply manipulative way; unhinged psychopaths aren’t the only ones who appreciate Bach or the Symphonie fantastique. Zbigniew Preisner's scores are woven into the fabric of the films as an important part of people’s lives.

Part of the joy for me in Three Colors (besides the three beautiful women cast in each movie) is that composed music is significant in Kieslowski’s world. It isn’t used as window dressing or in a cheaply manipulative way; unhinged psychopaths aren’t the only ones who appreciate Bach or the Symphonie fantastique. Zbigniew Preisner's scores are woven into the fabric of the films as an important part of people’s lives.

Juliette Binoche’s husband in Blue is a composer who is considered a national treasure. When he dies in a car wreck, his death is mourned by an entire country awaiting his next work. (Whether Boulez would have allowed another composer – and a tonal one! – such ascendancy in France without towing the avant-garde line doesn’t come up in the film.) Binoche’s character tries to block out music as part of the isolation she builds to hold off - or hold in - her grief. The music invades her attempted solitude, and eventually becomes an agent for her future healing.

Irène Jacob’s character in Red is moved to tears by music she comes across on the radio, eventually finding the recording in a store. The music – by a fictional Dutch composer Van den Budenmayer* – is a connection she shares (unbeknownst to her) with an eavesdropping former judge whom she befriends. The character Valentin is a kind of stand-in for open-hearted innocence that Kieslowski suggests is an integral aspect (buried under deep cynicism in the judge) of fraternité. When the music affects her, it touches that part in all of us.

Classical music has less of a direct role in White, though the main composition – a tango for string sextet (reminiscent in spirit and scoring of Tchaikovsky’s Souvenir of Florence) – gives a vital clue to Kieslowski’s approach to the concept of egalité.

* Kieslowski and Preisner invented Van den Budenmayer as an in-joke, making him Dutch simply because they liked Holland. Apparently Kieslowski was always pleased when people asked where they could find recordings of Van den Budenmayer’s music, and Preisner actually fielded allegations that he had plagiarized the composer he helped make up.

Another tangentially on-topic film went into the old DVD player the other night: Werner Herzog’s Fitzcarraldo (1982).

Another tangentially on-topic film went into the old DVD player the other night: Werner Herzog’s Fitzcarraldo (1982). While the crew carries various guns and knives, Fitzcarraldo is armed with a stack of Caruso records and an unshakeable belief in his dream. When war drums echo through the jungle, he responds by cranking up his Victrola and serenading the natives with Verdi. And it works. (To Herzog’s credit the native tribe that Fitzcarraldo encounters is treated sensitively and with intelligence. They never become a surrogate for a lost Western ideal, and their motives remain their own even as they undertake the bizarrely

While the crew carries various guns and knives, Fitzcarraldo is armed with a stack of Caruso records and an unshakeable belief in his dream. When war drums echo through the jungle, he responds by cranking up his Victrola and serenading the natives with Verdi. And it works. (To Herzog’s credit the native tribe that Fitzcarraldo encounters is treated sensitively and with intelligence. They never become a surrogate for a lost Western ideal, and their motives remain their own even as they undertake the bizarrely  On a side note, one of Fitzcarraldo’s Caruso records is the famous

On a side note, one of Fitzcarraldo’s Caruso records is the famous